Difference between revisions of "Understanding the Code"

Difference between revisions of "Understanding the Code"

(Created page with "{{Template:RPM Info}} __NOTOC__ {{DISPLAYTITLE:<span style="position: absolute; clip: rect(1px 1px 1px 1px); clip: rect(1px, 1px, 1px, 1px);">{{FULLPAGENAME}}</span>}} <div...") |

(→More than meets the eye) |

||

| (10 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Template:RPM Info}} | {{Template:RPM Info}} | ||

__NOTOC__ | __NOTOC__ | ||

| + | __NONUMBEREDHEADINGS__ | ||

{{DISPLAYTITLE:<span style="position: absolute; clip: rect(1px 1px 1px 1px); clip: rect(1px, 1px, 1px, 1px);">{{FULLPAGENAME}}</span>}} | {{DISPLAYTITLE:<span style="position: absolute; clip: rect(1px 1px 1px 1px); clip: rect(1px, 1px, 1px, 1px);">{{FULLPAGENAME}}</span>}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<big><big>Division E - General Information</big></big> | <big><big>Division E - General Information</big></big> | ||

<hr> | <hr> | ||

| − | <big><big><big><big><big> | + | <big><big><big><big><big>Understanding the British Columbia Building Code</big></big></big></big></big> |

| + | |||

| + | This is the first part of a multi-part series on the Building Code and roofing: | ||

| + | :Part 1: Understanding the BC Building Code | ||

| + | :Part 2: The Building Code and wind | ||

| + | :Part 3: Design Responsibility: from Code to Specification | ||

| + | You can find these articles in both the printed and digital editions of Roofing BC, the trade magazine published by the RCABC. You can also watch the video presentation, “Blown Away: Code Requirements for Membrane Roofs”, that addresses several articles in this series. | ||

| − | This | + | This article explores the origin and function of the British Columbia Building Code, how to read and understand the Code, and what it says about roof design and construction. While the material presented here is drawn from various government publications, it also reflects the writer’s own understanding of the Code – its structure, purpose and meaning. |

| − | + | The content on this page has been adapted from the original published article in [https://www.mediaedgemagazines.com/roofing-contractors-association-of-british-columbia-rcabc/rc211/''Roofing BC'' (Spring 2021)]. | |

| + | ==Introduction== | ||

Constructing a building is a complex task. It involves thousands of different materials and components, assembled into products and system by many people, both on the construction site and in shops and factories. The assembly and integration of these various materials and systems into a finished building requires tremendous coordination, negotiation, flexibility and constant adaptation to the weather, market forces, trade schedules and contractual commitments. When it is all done, the commissioned building must be safe, accessible, provide a healthy environment for people, energy efficient, and it must capably protect the building interior and those who live or work there from both the weather and seismic events. | Constructing a building is a complex task. It involves thousands of different materials and components, assembled into products and system by many people, both on the construction site and in shops and factories. The assembly and integration of these various materials and systems into a finished building requires tremendous coordination, negotiation, flexibility and constant adaptation to the weather, market forces, trade schedules and contractual commitments. When it is all done, the commissioned building must be safe, accessible, provide a healthy environment for people, energy efficient, and it must capably protect the building interior and those who live or work there from both the weather and seismic events. | ||

| − | Building construction involves many layers of responsibility. Owners, for example, have an overall responsibility for their projects – to determine what will be built, how it will conform to existing laws, and how they will select qualified advisors and builders. Designers are responsible to produce drawings and specifications that also comply with regulations and laws, and that reflect the interests of the owner. Contractors bear the responsibility of performing the work, scheduling trades, managing supplies, and constructing the building to align with the drawings and specifications. What ties them together in a common enterprise is the Building Code, which was developed to protect the public interest by establishing minimum requirements for safe, stable, and habitable buildings. | + | Building construction involves many layers of responsibility. Owners, for example, have an overall responsibility for their projects – to determine what will be built, how it will conform to existing laws, and how they will select qualified advisors and builders. Designers are responsible to produce drawings and specifications that also comply with regulations and laws, and that reflect the interests of the owner. Contractors bear the responsibility of performing the work, scheduling trades, managing supplies, and constructing the building to align with the drawings and specifications [[#Footnotes|<sup><small>1</small></sup>]]. What ties them together in a common enterprise is the Building Code, which was developed to protect the public interest by establishing minimum requirements for safe, stable, and habitable buildings. |

| − | + | ==The Code: building harmony and uniformity== | |

| + | [[File:Understanding the BCBC - Image 1 (VBBL).jpg|left|150px|link=https://free.bcpublications.ca/civix/content/public/vbbl2019/?xsl=/templates/browse.xsl]]<br clear=all> | ||

In British Columbia, nearly all building construction is governed by the British Columbia Building Code (the “Code”), an adaptation of the National Building Code of Canada (NBC). The City of Vancouver is an exception; as a Charter City with unique status across Canada, it operates under its own Building By-law, also an adaptation of the NBC. To understand what the Code is, and why it matters, we need to understand how it fits within the legislative framework established by government, and how the Code is developed. | In British Columbia, nearly all building construction is governed by the British Columbia Building Code (the “Code”), an adaptation of the National Building Code of Canada (NBC). The City of Vancouver is an exception; as a Charter City with unique status across Canada, it operates under its own Building By-law, also an adaptation of the NBC. To understand what the Code is, and why it matters, we need to understand how it fits within the legislative framework established by government, and how the Code is developed. | ||

| − | In Canada generally and in British Columbia specifically, the Code falls within a hierarchy of legislative tools used by government to standardize building construction. The Building Act in British Columbia is a statute that provides “control or directives on legal authority”. The Building Regulation is managed by the British Columbia Ministry of Farming, natural resources and industry and establishes consistent technical requirements under the authority of the Act for the construction of buildings. The Code is an example of such a “technical requirement” | + | In Canada generally and in British Columbia specifically, the Code falls within a hierarchy of legislative tools used by government to standardize building construction. The Building Act in British Columbia is a statute that provides “control or directives on legal authority”[[#Footnotes|<sup><small>2</small></sup>]]. The Building Regulation is managed by the British Columbia Ministry of Farming, natural resources and industry and establishes consistent technical requirements under the authority of the Act for the construction of buildings. The Code is an example of such a “technical requirement”. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Codes have a higher authority over standards. A code is mandatory, “broad in scope and is intended to carry the force of law when adopted by a provincial, territorial or municipal authority…”[[#Footnotes|<sup><small>3</small></sup>]]. Standards, which may be voluntary or mandatory, do not posses the strength of the Code, but may be referenced within the Code and “establish accepted practices, technical requirements, and terminologies for diverse fields”. Numerous CSA, CGSB, ASTM, UL/ULC and industry standards are referenced throughout the Code and support its objectives. For example, ASTM E 779, “Standard Test Method for Determining Air Leakage Rate by Fan Pressurization” is referenced in the British Columbia Building Code, Division B, Part 10, 10.2.3.5 Building Envelope Airtightness Testing. Some standards do not become legal requirements but are simply used in an industry as a recognized ‘articulation of “good practice”’[[#Footnotes|<sup><small>4</small></sup>]]. The Standards in the RCABC Roofing Practices Manual are often referenced this way. | |

| − | + | While the Code is the responsibility of the Ministry (and managed by the Building and Safety Standard Branch), the Code cannot be amended at the provincial level. In fact, the Building and Safety Standard Branch offers no Code change mechanism to the public. This is because the Code is an “offspring” of the NBC, the model building code (template) on which nearly all provincial building codes are based (Quebec operates under its own Code de construction du Québec). The NBC has jurisdiction across the country only with respect to federal institutions and buildings that are owned and managed by ministries of the federal government (National Defence, for example). Beyond that, the NBC currently has no legal status in provinces and territories who adopt and adapt it to suit specific regional requirements[[#Footnotes|<sup><small>5</small></sup>]]. | |

| − | Members of the Commission are volunteers, selected from across Canada for their particular interests and expertise, and represent the broad geographical and technical spectrum of the country. Together, they oversee the preparation and revision of several model codes used across Canada, including | + | The NBC was first published in 1941, and then substantially revised in response to a post-war construction boom. The Code as we know it is consensus-based, developed by numerous federal, provincial and industry stakeholders under the direction of the Canadian Commission on Building and Fire Codes (CCBFC). The Commission was established in 1991 by the National Research Council of Canada (NRC), and maintains other key national model codes published by Codes Canada (a division of the NRC). Members of the Commission are volunteers, selected from across Canada for their particular interests and expertise, and represent the broad geographical and technical spectrum of the country. Together, they oversee the preparation and revision of several model codes used across Canada, including |

| − | * the National Building Code | + | :*the '''National Building Code''' |

| − | * the National Plumbing Code | + | :*the '''National Plumbing Code''' |

| − | * the National Energy Code of Canada for Buildings (NECB), and | + | :*the '''National Energy Code of Canada for Buildings (NECB)''', and |

| − | * the National Fire Code. | + | :*the '''National Fire Code'''. |

| − | + | [[File:Understanding the BCBC - Image 3 (National Codes).jpg|left|500px|link=https://free.bcpublications.ca/civix/content/public/vbbl2019/?xsl=/templates/browse.xsl]]<br clear=all> | |

| − | The Commission also oversees the development and revisions of numerous guidance documents. The Canadian Electrical (CE) Code is prepared separately by the Committee on the Canadian Electrical Code, Part I, under the auspices of the CSA Group (formerly the Canadian Standards Association, or CSA); the CSA Group is accredited by the Standards Council Canada to develop the CE Code and numerous standards. | + | The Commission also oversees the development and revisions of numerous guidance documents. The Canadian Electrical (CE) Code is prepared separately by the Committee on the Canadian Electrical Code, Part I, under the auspices of the CSA Group (formerly the Canadian Standards Association, or CSA); the CSA Group is accredited by the Standards Council Canada to develop the CE Code and numerous standards[[#Footnotes|<sup><small>6</small></sup>]]. |

New and revised language in the NBC is the responsibility of nine Standing Committees established by the Commission, each overseeing a particular aspect of the NBC. With input from more than forty task groups and working groups, they work to sift through, evaluate and integrate into the NBC or related documents (such as user guides) all policy advice received from the provinces and territories, submitted through their Commission representatives. The result is a consensus-based Code used as a model by Canadian provinces and territories. | New and revised language in the NBC is the responsibility of nine Standing Committees established by the Commission, each overseeing a particular aspect of the NBC. With input from more than forty task groups and working groups, they work to sift through, evaluate and integrate into the NBC or related documents (such as user guides) all policy advice received from the provinces and territories, submitted through their Commission representatives. The result is a consensus-based Code used as a model by Canadian provinces and territories. | ||

Although the nine Standing Committees are not necessarily aligned with the nine Parts of the Code, they address key subject matters that are integrated into each Part: | Although the nine Standing Committees are not necessarily aligned with the nine Parts of the Code, they address key subject matters that are integrated into each Part: | ||

| − | * HVAC and Plumbing (SC-HP) | + | :*HVAC and Plumbing (SC-HP) |

| − | * Energy Efficiency (SC-EE) | + | :*Energy Efficiency (SC-EE) |

| − | * Earthquake Design (SC-ED) | + | :*Earthquake Design (SC-ED) |

| − | * Environmental Separation (SC-ES) | + | :*Environmental Separation (SC-ES) |

| − | * Fire Protection (SC-FP) | + | :*Fire Protection (SC-FP) |

| − | * Hazardous Materials and Activities (SC-HMA) | + | :*Hazardous Materials and Activities (SC-HMA) |

| − | * Housing and Small Buildings (SC-HSB) | + | :*Housing and Small Buildings (SC-HSB) |

| − | * Structural Design (SC-SD) | + | :*Structural Design (SC-SD) |

| − | * Use and Egress (SC-UE) | + | :*Use and Egress (SC-UE) |

| + | [[File:Understanding the BCBC - Image 4 (NRC-CCBFC).jpg|left|500px|link=https://free.bcpublications.ca/civix/content/public/vbbl2019/?xsl=/templates/browse.xsl]]<br clear=all> | ||

The NBC is revised and republished every five years. The British Columbia code cycle is offset from the NBC cycle by two years so that each iteration of the Code can be properly considered by the Building and Safety Standard Branch and, if necessary, revised to suit our provincial context and government mandates. | The NBC is revised and republished every five years. The British Columbia code cycle is offset from the NBC cycle by two years so that each iteration of the Code can be properly considered by the Building and Safety Standard Branch and, if necessary, revised to suit our provincial context and government mandates. | ||

| − | In British Columbia, the Code is enforced by local governments who have the freedom to establish additional requirements on ‘unrestricted’ matters . The NBC has jurisdiction across the country only with respect to federal institutions and buildings that are owned and managed by ministries of the government (National Defence, for example). | + | In British Columbia, the Code is enforced by local governments who have the freedom to establish additional requirements on ‘unrestricted’ matters[[#Footnotes|<sup><small>7</small></sup>]]. The NBC has jurisdiction across the country only with respect to federal institutions and buildings that are owned and managed by ministries of the government (National Defence, for example). |

| − | + | ||

We can be grateful for the Code and the uniformity it brings to building construction in Canada. In the U.S., many states rely on the International Building Code (IBC), but there appears to be no uniformity across the country and some states mandate compliance with several codes, resulting in a complex regulatory environment for builders. | We can be grateful for the Code and the uniformity it brings to building construction in Canada. In the U.S., many states rely on the International Building Code (IBC), but there appears to be no uniformity across the country and some states mandate compliance with several codes, resulting in a complex regulatory environment for builders. | ||

| − | + | ==How the Code is organized== | |

| + | [[File:Understanding the BCBC - Image 5 (BCBC-BCPC).jpg|left|200px]]<br clear=all> | ||

Most of us know the Code as a single book (or electronic document), but that is in fact Book I of a two- volume document collectively called the British Columbia Building Code. Book II of the British Columbia Building Code is the BC Plumbing Code. Each is published as a separate document. For the sake of simplicity, I will restrict further discussion to Volume I and refer to it simply as “the Code”. | Most of us know the Code as a single book (or electronic document), but that is in fact Book I of a two- volume document collectively called the British Columbia Building Code. Book II of the British Columbia Building Code is the BC Plumbing Code. Each is published as a separate document. For the sake of simplicity, I will restrict further discussion to Volume I and refer to it simply as “the Code”. | ||

The Code is now free to anyone online, without a subscription. Any text that carried over from the 2012 Code remains as black type. New material is shown in blue and is clearly marked. The Code is constantly being revised, and addenda can be obtained from the Errata and Revisions page of the British Columbia Codes website. | The Code is now free to anyone online, without a subscription. Any text that carried over from the 2012 Code remains as black type. New material is shown in blue and is clearly marked. The Code is constantly being revised, and addenda can be obtained from the Errata and Revisions page of the British Columbia Codes website. | ||

| − | |||

To understand how to read the Code, you need to understand and appreciate its organization, which the Roofing Practices Manual is loosely modelled after. The Code is arranged in three divisions, and each division is further segregated into Parts (for an explanation of the nomenclature used in the Code, read the Code Preface): | To understand how to read the Code, you need to understand and appreciate its organization, which the Roofing Practices Manual is loosely modelled after. The Code is arranged in three divisions, and each division is further segregated into Parts (for an explanation of the nomenclature used in the Code, read the Code Preface): | ||

<ol> | <ol> | ||

| − | <li>Division A, titled “Compliance, Objectives and Functional Statements”, defines the scope of the Code, “outlines the main objectives and functional statements for technical building requirements”, and “explains why a requirement must be met and how to evaluate other ways to meet the acceptable requirements through alternative solutions.” | + | <li>Division A, titled “Compliance, Objectives and Functional Statements”, defines the scope of the Code, “outlines the main objectives and functional statements for technical building requirements”, and “explains why a requirement must be met and how to evaluate other ways to meet the acceptable requirements through alternative solutions.”[[#Footnotes|<sup><small>8</small></sup>]] |

<li>Division B is the “how to” or technical division of the Code. Called “Acceptable Solutions”, Division B identifies the technical means by which a building can satisfy the requirements of the Code. Acceptable solutions include notes that link Division B back to the objectives and functional statements in Division A. | <li>Division B is the “how to” or technical division of the Code. Called “Acceptable Solutions”, Division B identifies the technical means by which a building can satisfy the requirements of the Code. Acceptable solutions include notes that link Division B back to the objectives and functional statements in Division A. | ||

| − | <li>Division C, “Administrative Provisions”, articulates who is responsible for building design, and provides guidance when an alternative solution to the Code is necessary. Many provinces and territories establish their own administrative provisions, including British Columbia. | + | <li>Division C, “Administrative Provisions”, articulates who is responsible for building design, and provides guidance when an alternative solution to the Code is necessary. Many provinces and territories establish their own administrative provisions, including British Columbia.[[#Footnotes|<sup><small>9</small></sup>]] |

</li></ol> | </li></ol> | ||

Each Division is arranged into Parts, and each Part is further arranged into sections, sub-sections, articles and so forth. By such an arrangement, the reader can ‘drill down’ into the Code and obtain guidance. | Each Division is arranged into Parts, and each Part is further arranged into sections, sub-sections, articles and so forth. By such an arrangement, the reader can ‘drill down’ into the Code and obtain guidance. | ||

| − | + | ==A Code with purpose== | |

| − | The Code is not a quality control manual. Quality, in fact, falls outside the mandate of the Code. Nor does the Code deal with every issue that could fall within its scope. Rather, the purpose of the Code is to mandate building fire safety, structural soundness and stability, occupant comfort and interior environment safety, ingress and egress, and the control of a building’s interior climate. These broad objectives are clearly articulated in Division A and are fashioned around statements that identify “undesirable situations and their consequences, which the Code aims to avoid occurring in buildings”. These “objective statements” aim to “limit the probability” of an undesirable situation or “unacceptable risk” and are what the Code refers to as “entirely qualitative”. As such, they are not intended to be used by themselves for designing or approving the construction of a building. | + | The Code is not a quality control manual. Quality, in fact, falls outside the mandate of the Code. Nor does the Code deal with every issue that could fall within its scope. Rather, the purpose of the Code is to mandate building fire safety, structural soundness and stability, occupant comfort and interior environment safety, ingress and egress, and the control of a building’s interior climate. These broad objectives are clearly articulated in Division A and are fashioned around statements that identify “undesirable situations and their consequences, which the Code aims to avoid occurring in buildings”[[#Footnotes|<sup><small>10</small></sup>]]. These “objective statements” aim to “limit the probability” of an undesirable situation or “unacceptable risk” and are what the Code refers to as “entirely qualitative”. As such, they are not intended to be used by themselves for designing or approving the construction of a building. |

Because the Code does not deal with quality (which is left to regulations or standards that industry often develops and administers), it is bereft of any statements about best practices. Rather, the Code permits certain kinds of materials and directs, in the broadest of terms, how they can be arranged to satisfy the minimum requirements established by the Objectives. Where structural loads impact the design and construction of building enclosure systems, the Code provides guidance in Division B, and in the notes. | Because the Code does not deal with quality (which is left to regulations or standards that industry often develops and administers), it is bereft of any statements about best practices. Rather, the Code permits certain kinds of materials and directs, in the broadest of terms, how they can be arranged to satisfy the minimum requirements established by the Objectives. Where structural loads impact the design and construction of building enclosure systems, the Code provides guidance in Division B, and in the notes. | ||

| − | + | ==Prescriptive or performance-based?== | |

Until December 2018, the Code offered two paths by which a design could conform to its requirements: the prescriptive path and the performance -based path. The prescriptive pathway was less onerous than the performance-based path former because it focused on the characteristics of individual components or systems of a building, not on how the building as a “system of systems” performed. For example, insulation tables specified minimum thermal resistance values, depending on where the insulation was installed, but these requirements were not integrated with the design and minimum requirements for the heating and ventilating systems of the building (Part 10), nor with the requirements for air controls (Part 5). “Air barrier systems” had to be continuous between various materials and systems, but the Code appeared to be silent on how to verify “continuity”. | Until December 2018, the Code offered two paths by which a design could conform to its requirements: the prescriptive path and the performance -based path. The prescriptive pathway was less onerous than the performance-based path former because it focused on the characteristics of individual components or systems of a building, not on how the building as a “system of systems” performed. For example, insulation tables specified minimum thermal resistance values, depending on where the insulation was installed, but these requirements were not integrated with the design and minimum requirements for the heating and ventilating systems of the building (Part 10), nor with the requirements for air controls (Part 5). “Air barrier systems” had to be continuous between various materials and systems, but the Code appeared to be silent on how to verify “continuity”. | ||

With the release of the 2018 Code, all of that changed. The prescriptive option vanished, and the Code shifted entirely toward specific, measurable performance criteria, driven in large part by a singular change in perspective: making buildings more energy efficient by focusing on the measurable continuity and thermal performance of the entire building enclosure (see my article, Stepping up our game, in the Fall 2018 issue of BC Roofing). By doing this, the Code allowed for variables in system design, provided they achieved minimum performance characteristics. This also meant that energy efficient mechanical systems became one strategy among several, to make buildings more energy efficient. | With the release of the 2018 Code, all of that changed. The prescriptive option vanished, and the Code shifted entirely toward specific, measurable performance criteria, driven in large part by a singular change in perspective: making buildings more energy efficient by focusing on the measurable continuity and thermal performance of the entire building enclosure (see my article, Stepping up our game, in the Fall 2018 issue of BC Roofing). By doing this, the Code allowed for variables in system design, provided they achieved minimum performance characteristics. This also meant that energy efficient mechanical systems became one strategy among several, to make buildings more energy efficient. | ||

| − | + | ||

This change in perspective dramatically impacted roof system design and strongly linked formerly nebulous connections between Part 4, 5 and 10 in Division B. For example, the 2018 Code introduced expanded calculations in Part 4 concerning the determination of Specified Wind Loads. Part 5 (including the notes to Part 5) added made-in-Canada solutions for keeping out the weather while simultaneously satisfying the structural design criteria in Part 4; that guidance was largely absent from earlier editions of the Code, which led designers to use whatever could be deemed ‘Code-compliant’, including the citation of standards and specifications published by FM Global. And because the Code placed a heavier emphasis on the measurable continuity of air and vapour controls (Part 5 and Part 10), the design and construction of the roof took on more significance as a key facet of the entire building enclosure. I will have more to say about these changes in future articles. | This change in perspective dramatically impacted roof system design and strongly linked formerly nebulous connections between Part 4, 5 and 10 in Division B. For example, the 2018 Code introduced expanded calculations in Part 4 concerning the determination of Specified Wind Loads. Part 5 (including the notes to Part 5) added made-in-Canada solutions for keeping out the weather while simultaneously satisfying the structural design criteria in Part 4; that guidance was largely absent from earlier editions of the Code, which led designers to use whatever could be deemed ‘Code-compliant’, including the citation of standards and specifications published by FM Global. And because the Code placed a heavier emphasis on the measurable continuity of air and vapour controls (Part 5 and Part 10), the design and construction of the roof took on more significance as a key facet of the entire building enclosure. I will have more to say about these changes in future articles. | ||

| − | + | ==Complexity and integration== | |

If you are new to reading the Code, the first thing you must understand is that while the Code is clearly organized, it is complex and integrated among and across divisions and parts. Most readers focus on the “how to” technical requirements of Division B. But if you read the Code carefully, you will see that every Part in Division B begins with a cross-reference to either Division A or Division C requirements. Become familiar with entire Code, not only the divisions or parts that seem applicable to a specific subject or issue. | If you are new to reading the Code, the first thing you must understand is that while the Code is clearly organized, it is complex and integrated among and across divisions and parts. Most readers focus on the “how to” technical requirements of Division B. But if you read the Code carefully, you will see that every Part in Division B begins with a cross-reference to either Division A or Division C requirements. Become familiar with entire Code, not only the divisions or parts that seem applicable to a specific subject or issue. | ||

| − | In basic terms, the Code addresses two kinds of buildings. A “Part 3” building broadly refers to various large institutional, commercial, and industrial structures built to comply with Division B, Part 3 and various other Parts in that division (''British Columbia Building Code, Division A, Part 1'', '''1.3.3 Application of Division B''', and ''Division B, Part 3'', '''3.1.2 Classification of Buildings or Parts of Buildings by Major Occupancy'''). A “Part 9” building alternatively refers to housing and small buildings up to three storeys in height and no larger than 600 m2 in area, which are governed by Part 9 in Division B. This latter category includes single family dwellings, multi-family residential buildings and buildings with business occupancies. In some cases, structural requirements in Division B, Part 4 apply to “Part 9” design requirements (see ''9.4.1 Structural Design Requirements and Application Limitations''). It is also important to recognize that Parts 1, 7, 8 and 10 also apply to “Part 9” buildings (''British Columbia Building Code, Division A, Part 1'' | + | In basic terms, the Code addresses two kinds of buildings. A “Part 3” building broadly refers to various large institutional, commercial, and industrial structures built to comply with Division B, Part 3 and various other Parts in that division (''British Columbia Building Code, Division A, Part 1'', '''1.3.3. Application of Division B''', and ''Division B, Part 3'', '''3.1.2 Classification of Buildings or Parts of Buildings by Major Occupancy'''). A “Part 9” building alternatively refers to housing and small buildings up to three storeys in height and no larger than 600 m2 in area, which are governed by Part 9 in Division B. This latter category includes single family dwellings, multi-family residential buildings and buildings with business occupancies. In some cases, structural requirements in Division B, Part 4 apply to “Part 9” design requirements (see ''9.4.1 Structural Design Requirements and Application Limitations''). It is also important to recognize that Parts 1, 7, 8 and 10 also apply to “Part 9” buildings (''British Columbia Building Code, Division A, Part 1'': Article 1.3.3.1., '''Application of Parts 1, 7, 8 and 10'''). |

| + | |||

| + | ==More than meets the eye== | ||

| + | Roofs now do more than simply keep the weather out; they protect the integrity of the whole building and serve as a key component in the entire building enclosure to control the movement of air, moisture, and sound in and out of the structure. To do this, they need to stay where they are built, and to stay where they are built, they must be designed and constructed to comply with the Code. By collaborating and learning together, the Design Authority and roofing contractor can make it work. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the next article of this series, we explore the subject of roof design and construction for Part 3 buildings and examine what the Code has to say about structural loading and roof membrane system selection. Additionally, we'll offer some ways in which design specifications can navigate the complexities of Code compliance, owner interests and performance criteria. | ||

| + | <hr> | ||

| + | ===Footnotes=== | ||

| + | <sup><small>1</small></sup> National Research Council Canada, Canada’s construction system – The context for model codes (https://nrc.canada.ca/en/certifications-evaluations-standards/codes-canada/canadas-construction-system-context-model-codes (Updated 2018)).<br> | ||

| + | <sup><small>2</small></sup> Ibid.<br> | ||

| + | <sup><small>3</small></sup> Standards Council Canada, Types of Standards (https://www.scc.ca/en/types-standards).<br> | ||

| + | <sup><small>4</small></sup> National Research Council Canada, Canada’s National Model Codes Development System.<br> | ||

| + | <sup><small>5</small></sup> National Research Council Canada, Frequently Asked Questions.<br> | ||

| + | <sup><small>6</small></sup> Standards Council of Canada, Directory of Accredited Certification Bodies (https://www.scc.ca/en/accreditation/programs/standards/directory).<br> | ||

| + | <sup><small>7</small></sup> Building Act, Government of British Columbia (https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/industry/construction-industry/building-codes-standards/building-act).<br> | ||

| + | <sup><small>8</small></sup> Government of British Columbia, BC Codes (https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/industry/construction-industry/building-codes-standards/bc-codes#BCBC).<br> | ||

| + | <sup><small>9</small></sup> BCBC, Preface: Structure of Objective-Based Codes (https://free.bcpublications.ca/civix/document/id/public/bcbc2018/bcbc_2018pre).<br> | ||

| + | <sup><small>10</small></sup> BCBC, Preface: Objective-Based Code Format (https://free.bcpublications.ca/civix/document/id/public/bcbc2018/bcbc_2018pre).<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-12"> | ||

| + | <hr> | ||

| − | = | + | [[Main Page | <i class="fa fa-home fa"></i> Home]] |

| − | + | </div> | |

| − | + | {{Tempate:RPM Page Footer with Copyright and Current Date}} | |

Latest revision as of 16:32, 16 March 2023

Division E - General Information

Understanding the British Columbia Building Code

This is the first part of a multi-part series on the Building Code and roofing:

- Part 1: Understanding the BC Building Code

- Part 2: The Building Code and wind

- Part 3: Design Responsibility: from Code to Specification

You can find these articles in both the printed and digital editions of Roofing BC, the trade magazine published by the RCABC. You can also watch the video presentation, “Blown Away: Code Requirements for Membrane Roofs”, that addresses several articles in this series.

This article explores the origin and function of the British Columbia Building Code, how to read and understand the Code, and what it says about roof design and construction. While the material presented here is drawn from various government publications, it also reflects the writer’s own understanding of the Code – its structure, purpose and meaning.

The content on this page has been adapted from the original published article in Roofing BC (Spring 2021).

Introduction

Constructing a building is a complex task. It involves thousands of different materials and components, assembled into products and system by many people, both on the construction site and in shops and factories. The assembly and integration of these various materials and systems into a finished building requires tremendous coordination, negotiation, flexibility and constant adaptation to the weather, market forces, trade schedules and contractual commitments. When it is all done, the commissioned building must be safe, accessible, provide a healthy environment for people, energy efficient, and it must capably protect the building interior and those who live or work there from both the weather and seismic events.

Building construction involves many layers of responsibility. Owners, for example, have an overall responsibility for their projects – to determine what will be built, how it will conform to existing laws, and how they will select qualified advisors and builders. Designers are responsible to produce drawings and specifications that also comply with regulations and laws, and that reflect the interests of the owner. Contractors bear the responsibility of performing the work, scheduling trades, managing supplies, and constructing the building to align with the drawings and specifications 1. What ties them together in a common enterprise is the Building Code, which was developed to protect the public interest by establishing minimum requirements for safe, stable, and habitable buildings.

The Code: building harmony and uniformity

In British Columbia, nearly all building construction is governed by the British Columbia Building Code (the “Code”), an adaptation of the National Building Code of Canada (NBC). The City of Vancouver is an exception; as a Charter City with unique status across Canada, it operates under its own Building By-law, also an adaptation of the NBC. To understand what the Code is, and why it matters, we need to understand how it fits within the legislative framework established by government, and how the Code is developed.

In Canada generally and in British Columbia specifically, the Code falls within a hierarchy of legislative tools used by government to standardize building construction. The Building Act in British Columbia is a statute that provides “control or directives on legal authority”2. The Building Regulation is managed by the British Columbia Ministry of Farming, natural resources and industry and establishes consistent technical requirements under the authority of the Act for the construction of buildings. The Code is an example of such a “technical requirement”.

Codes have a higher authority over standards. A code is mandatory, “broad in scope and is intended to carry the force of law when adopted by a provincial, territorial or municipal authority…”3. Standards, which may be voluntary or mandatory, do not posses the strength of the Code, but may be referenced within the Code and “establish accepted practices, technical requirements, and terminologies for diverse fields”. Numerous CSA, CGSB, ASTM, UL/ULC and industry standards are referenced throughout the Code and support its objectives. For example, ASTM E 779, “Standard Test Method for Determining Air Leakage Rate by Fan Pressurization” is referenced in the British Columbia Building Code, Division B, Part 10, 10.2.3.5 Building Envelope Airtightness Testing. Some standards do not become legal requirements but are simply used in an industry as a recognized ‘articulation of “good practice”’4. The Standards in the RCABC Roofing Practices Manual are often referenced this way.

While the Code is the responsibility of the Ministry (and managed by the Building and Safety Standard Branch), the Code cannot be amended at the provincial level. In fact, the Building and Safety Standard Branch offers no Code change mechanism to the public. This is because the Code is an “offspring” of the NBC, the model building code (template) on which nearly all provincial building codes are based (Quebec operates under its own Code de construction du Québec). The NBC has jurisdiction across the country only with respect to federal institutions and buildings that are owned and managed by ministries of the federal government (National Defence, for example). Beyond that, the NBC currently has no legal status in provinces and territories who adopt and adapt it to suit specific regional requirements5.

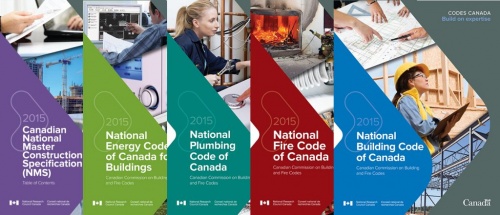

The NBC was first published in 1941, and then substantially revised in response to a post-war construction boom. The Code as we know it is consensus-based, developed by numerous federal, provincial and industry stakeholders under the direction of the Canadian Commission on Building and Fire Codes (CCBFC). The Commission was established in 1991 by the National Research Council of Canada (NRC), and maintains other key national model codes published by Codes Canada (a division of the NRC). Members of the Commission are volunteers, selected from across Canada for their particular interests and expertise, and represent the broad geographical and technical spectrum of the country. Together, they oversee the preparation and revision of several model codes used across Canada, including

- the National Building Code

- the National Plumbing Code

- the National Energy Code of Canada for Buildings (NECB), and

- the National Fire Code.

The Commission also oversees the development and revisions of numerous guidance documents. The Canadian Electrical (CE) Code is prepared separately by the Committee on the Canadian Electrical Code, Part I, under the auspices of the CSA Group (formerly the Canadian Standards Association, or CSA); the CSA Group is accredited by the Standards Council Canada to develop the CE Code and numerous standards6.

New and revised language in the NBC is the responsibility of nine Standing Committees established by the Commission, each overseeing a particular aspect of the NBC. With input from more than forty task groups and working groups, they work to sift through, evaluate and integrate into the NBC or related documents (such as user guides) all policy advice received from the provinces and territories, submitted through their Commission representatives. The result is a consensus-based Code used as a model by Canadian provinces and territories.

Although the nine Standing Committees are not necessarily aligned with the nine Parts of the Code, they address key subject matters that are integrated into each Part:

- HVAC and Plumbing (SC-HP)

- Energy Efficiency (SC-EE)

- Earthquake Design (SC-ED)

- Environmental Separation (SC-ES)

- Fire Protection (SC-FP)

- Hazardous Materials and Activities (SC-HMA)

- Housing and Small Buildings (SC-HSB)

- Structural Design (SC-SD)

- Use and Egress (SC-UE)

The NBC is revised and republished every five years. The British Columbia code cycle is offset from the NBC cycle by two years so that each iteration of the Code can be properly considered by the Building and Safety Standard Branch and, if necessary, revised to suit our provincial context and government mandates.

In British Columbia, the Code is enforced by local governments who have the freedom to establish additional requirements on ‘unrestricted’ matters7. The NBC has jurisdiction across the country only with respect to federal institutions and buildings that are owned and managed by ministries of the government (National Defence, for example).

We can be grateful for the Code and the uniformity it brings to building construction in Canada. In the U.S., many states rely on the International Building Code (IBC), but there appears to be no uniformity across the country and some states mandate compliance with several codes, resulting in a complex regulatory environment for builders.

How the Code is organized

Most of us know the Code as a single book (or electronic document), but that is in fact Book I of a two- volume document collectively called the British Columbia Building Code. Book II of the British Columbia Building Code is the BC Plumbing Code. Each is published as a separate document. For the sake of simplicity, I will restrict further discussion to Volume I and refer to it simply as “the Code”.

The Code is now free to anyone online, without a subscription. Any text that carried over from the 2012 Code remains as black type. New material is shown in blue and is clearly marked. The Code is constantly being revised, and addenda can be obtained from the Errata and Revisions page of the British Columbia Codes website. To understand how to read the Code, you need to understand and appreciate its organization, which the Roofing Practices Manual is loosely modelled after. The Code is arranged in three divisions, and each division is further segregated into Parts (for an explanation of the nomenclature used in the Code, read the Code Preface):

- Division A, titled “Compliance, Objectives and Functional Statements”, defines the scope of the Code, “outlines the main objectives and functional statements for technical building requirements”, and “explains why a requirement must be met and how to evaluate other ways to meet the acceptable requirements through alternative solutions.”8

- Division B is the “how to” or technical division of the Code. Called “Acceptable Solutions”, Division B identifies the technical means by which a building can satisfy the requirements of the Code. Acceptable solutions include notes that link Division B back to the objectives and functional statements in Division A.

- Division C, “Administrative Provisions”, articulates who is responsible for building design, and provides guidance when an alternative solution to the Code is necessary. Many provinces and territories establish their own administrative provisions, including British Columbia.9

Each Division is arranged into Parts, and each Part is further arranged into sections, sub-sections, articles and so forth. By such an arrangement, the reader can ‘drill down’ into the Code and obtain guidance.

A Code with purpose

The Code is not a quality control manual. Quality, in fact, falls outside the mandate of the Code. Nor does the Code deal with every issue that could fall within its scope. Rather, the purpose of the Code is to mandate building fire safety, structural soundness and stability, occupant comfort and interior environment safety, ingress and egress, and the control of a building’s interior climate. These broad objectives are clearly articulated in Division A and are fashioned around statements that identify “undesirable situations and their consequences, which the Code aims to avoid occurring in buildings”10. These “objective statements” aim to “limit the probability” of an undesirable situation or “unacceptable risk” and are what the Code refers to as “entirely qualitative”. As such, they are not intended to be used by themselves for designing or approving the construction of a building.

Because the Code does not deal with quality (which is left to regulations or standards that industry often develops and administers), it is bereft of any statements about best practices. Rather, the Code permits certain kinds of materials and directs, in the broadest of terms, how they can be arranged to satisfy the minimum requirements established by the Objectives. Where structural loads impact the design and construction of building enclosure systems, the Code provides guidance in Division B, and in the notes.

Prescriptive or performance-based?

Until December 2018, the Code offered two paths by which a design could conform to its requirements: the prescriptive path and the performance -based path. The prescriptive pathway was less onerous than the performance-based path former because it focused on the characteristics of individual components or systems of a building, not on how the building as a “system of systems” performed. For example, insulation tables specified minimum thermal resistance values, depending on where the insulation was installed, but these requirements were not integrated with the design and minimum requirements for the heating and ventilating systems of the building (Part 10), nor with the requirements for air controls (Part 5). “Air barrier systems” had to be continuous between various materials and systems, but the Code appeared to be silent on how to verify “continuity”.

With the release of the 2018 Code, all of that changed. The prescriptive option vanished, and the Code shifted entirely toward specific, measurable performance criteria, driven in large part by a singular change in perspective: making buildings more energy efficient by focusing on the measurable continuity and thermal performance of the entire building enclosure (see my article, Stepping up our game, in the Fall 2018 issue of BC Roofing). By doing this, the Code allowed for variables in system design, provided they achieved minimum performance characteristics. This also meant that energy efficient mechanical systems became one strategy among several, to make buildings more energy efficient.

This change in perspective dramatically impacted roof system design and strongly linked formerly nebulous connections between Part 4, 5 and 10 in Division B. For example, the 2018 Code introduced expanded calculations in Part 4 concerning the determination of Specified Wind Loads. Part 5 (including the notes to Part 5) added made-in-Canada solutions for keeping out the weather while simultaneously satisfying the structural design criteria in Part 4; that guidance was largely absent from earlier editions of the Code, which led designers to use whatever could be deemed ‘Code-compliant’, including the citation of standards and specifications published by FM Global. And because the Code placed a heavier emphasis on the measurable continuity of air and vapour controls (Part 5 and Part 10), the design and construction of the roof took on more significance as a key facet of the entire building enclosure. I will have more to say about these changes in future articles.

Complexity and integration

If you are new to reading the Code, the first thing you must understand is that while the Code is clearly organized, it is complex and integrated among and across divisions and parts. Most readers focus on the “how to” technical requirements of Division B. But if you read the Code carefully, you will see that every Part in Division B begins with a cross-reference to either Division A or Division C requirements. Become familiar with entire Code, not only the divisions or parts that seem applicable to a specific subject or issue.

In basic terms, the Code addresses two kinds of buildings. A “Part 3” building broadly refers to various large institutional, commercial, and industrial structures built to comply with Division B, Part 3 and various other Parts in that division (British Columbia Building Code, Division A, Part 1, 1.3.3. Application of Division B, and Division B, Part 3, 3.1.2 Classification of Buildings or Parts of Buildings by Major Occupancy). A “Part 9” building alternatively refers to housing and small buildings up to three storeys in height and no larger than 600 m2 in area, which are governed by Part 9 in Division B. This latter category includes single family dwellings, multi-family residential buildings and buildings with business occupancies. In some cases, structural requirements in Division B, Part 4 apply to “Part 9” design requirements (see 9.4.1 Structural Design Requirements and Application Limitations). It is also important to recognize that Parts 1, 7, 8 and 10 also apply to “Part 9” buildings (British Columbia Building Code, Division A, Part 1: Article 1.3.3.1., Application of Parts 1, 7, 8 and 10).

More than meets the eye

Roofs now do more than simply keep the weather out; they protect the integrity of the whole building and serve as a key component in the entire building enclosure to control the movement of air, moisture, and sound in and out of the structure. To do this, they need to stay where they are built, and to stay where they are built, they must be designed and constructed to comply with the Code. By collaborating and learning together, the Design Authority and roofing contractor can make it work.

In the next article of this series, we explore the subject of roof design and construction for Part 3 buildings and examine what the Code has to say about structural loading and roof membrane system selection. Additionally, we'll offer some ways in which design specifications can navigate the complexities of Code compliance, owner interests and performance criteria.

Footnotes

1 National Research Council Canada, Canada’s construction system – The context for model codes (https://nrc.canada.ca/en/certifications-evaluations-standards/codes-canada/canadas-construction-system-context-model-codes (Updated 2018)).

2 Ibid.

3 Standards Council Canada, Types of Standards (https://www.scc.ca/en/types-standards).

4 National Research Council Canada, Canada’s National Model Codes Development System.

5 National Research Council Canada, Frequently Asked Questions.

6 Standards Council of Canada, Directory of Accredited Certification Bodies (https://www.scc.ca/en/accreditation/programs/standards/directory).

7 Building Act, Government of British Columbia (https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/industry/construction-industry/building-codes-standards/building-act).

8 Government of British Columbia, BC Codes (https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/industry/construction-industry/building-codes-standards/bc-codes#BCBC).

9 BCBC, Preface: Structure of Objective-Based Codes (https://free.bcpublications.ca/civix/document/id/public/bcbc2018/bcbc_2018pre).

10 BCBC, Preface: Objective-Based Code Format (https://free.bcpublications.ca/civix/document/id/public/bcbc2018/bcbc_2018pre).

© RCABC 2026

RoofStarTM is a registered Trademark of the RCABC.

No reproduction of this material, in whole or in part, is lawful without the expressed permission of the RCABC Guarantee Corp.